I came up with this fence design in 2005, and building it was the first project we did when we moved into our house. I wanted it to look good from both sides, and of course be reasonably solid. It's basically a set of horizontal rails that are used to sandwich the pickets. For a six ft. tall fence, I use three pairs of rails; 1x6 at the bottom, 1x4 in the middle, and 1x2 at the top. The rail configuration and picket width and spacing can be varied to change the style of the fence with little effort. Everything is held together with screws, which means it's pretty easy to take apart and repair or modify, and pre-drilling

every hole means no splitting. The panels are held to the posts by custom-made aluminum brackets, which are strong and non-corroding, while being invisible from one side and low profile from the other.

For the design I'm building here, the pickets alternate between full-width (5-1/2") and 1/3 width (1-3/4") and have a 3/4" gap between each one. I like this layout for fences that don't require the most privacy, and it makes a better wind screen than a solid fence. Yes, the gaps improve the wind performance. Go ask a physicist why.

So here's a step-by-step guide:

1. Set the posts. We have relatively solid clayey soils, so a simple protocol of digging a small hole and setting the post in concrete is plenty. I set an 8 ft. 4x4 (either pressure treated or quality cedar) about 21 in. down. That leaves 6'-3" above grade, enough for the post tops to rise an inch or two above the top of the fence panels. I always install the two corner posts first, let them set up, and then stretch a piece of mason line between them so that I can line up the remaining posts to that reference. No need to fill the hole right to the top. Even if you skip the curb (next step) you don't want to look at the top of a concrete plug around each post, so leave the surface a few inches below grade. Do slope the top of the concrete away from the post, however, to prevent water from pooling against the wood.

2. Pour a short concrete curb at the base. We just did this for the latest rendition of the fence across our north property line, but I'm going to go back and add this feature to some of the other segments. It prevents weeds and animals from crawling under, keeps the lowest wooden parts of the fence away from the soil, and makes for a much neater appearance. Plus it's easy and cheap. Scrape off three or four inches of soil (frost concerns are minimal to nonexistent here) and build forms by simply screwing 2x3's on each side of the posts. I put the tops about 2" above finished grade, and the bottom about 2" below. Make sure they're level across the width, and you can make them level or at a slight angle to follow ground contours between the posts. Mound soil along the outside of the forms to keep them from bowing out when you pour the concrete in.

|

| Filled and screeded flat. Note the water that floats to the surface. Do not disturb at this stage. |

When you fill the forms, work it into all the corners and vibrate it a bit by hand to get the bubbles out. Then just screed it flat by sawing back and forth with a scrap of lumber. A layer of water will appear at the surface, and then disappear after 30 minutes or so. At that point, the setting process should be far enough along that you can put nice curved edges on the top of the pour with an edging tool; just run it back and forth for a much improved final product. Unscrew the forms and rap them gently with a hammer to knock them loose after at least several hours.

|

| Time to remove the forms |

3. Make and install the aluminum brackets. I start with aluminum angle, 1"x1"x 1/6" thick. You'll need one for each end at each set of rails, and I cut them a little shorter than the rail material. So, 2 ea. 1-1/4", 2 ea. 3-1/4", and 2 ea. 5-1/4". Drill two screw clearance holes (just one on the 1-1/4" brackets), 3/16" in diameter, on each side. I center the ones that will be screwed to the posts, and put the ones that will go through the fence closer to the outer edge. That way, the screws won't be as close to the rail ends which will reduce the risk of splitting. Next I establish the top of the entire fence, usually by pulling a mason line level and marking each post. If the fence is built on a slope, I like to stair step each segment, but there's nothing wrong with building it at an angle, either. Come down 3/4" to allow for the top cap, and another 1/8" to allow for the bracket width being less than the top rail, and that gives the location for the top of the little top bracket. Attach the bracket to the post, 3/4" from the edge, with a #8 x 1" stainless steel pan head screw.

|

| A 3-1/4" Middle Bracket |

For the middle brackets, I just measure down some pleasing-to-the-eye distance and install all the brackets there. Usually about 14" to 16" looks good to me. For the bottom brackets, I measure up from the ground 1-1/4" to the lower edge of the bracket.

|

| Lower Bracket Installed - note the round, tooled edge on the curb |

4. Install the three rails on the "ugly" side. These are the ones that will have all the screw heads visible and also the side the brackets will be visible from. It's also the side you can take the fence apart from, so that's a consideration. They'll have to fit snugly between the brackets and screw heads, so I usually just hold the lumber up and mark the length in place. Screw them to the brackets with little #8 x 1/2" screws temporarily.

5. Install the pickets. This is the monotonous part. Measure from the bottom of the lower rail to the top of the top rail, and cut the pickets about 1/2" shorter. I use a Quick-Grip clamp, adjusting the height 1/8" or so below the top of the upper rail, and clamping at the middle rail. Use a bit with a countersink and drill a pilot hole through the rail and picket, in the center of the picket. Drive a 2" Deckmate screw through the rail, and just barely through the picket. It

really helps to have two drills for this. Move the clamp to the top rail, and repeat the process, making sure that the picket is vertical. Then clamp the picket to the bottom rail and put a screw in there. I use a spacer of some sort to keep the gap between each picket consistent, and check every third picket or so with a level to make sure I'm staying plumb.

|

| Picket Installation |

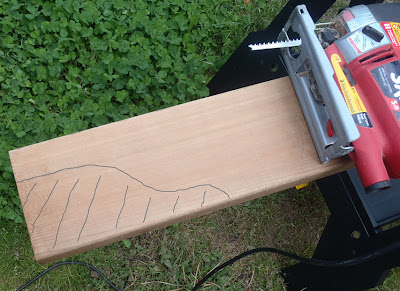

The last picket will be some odd width, and sometimes not even the same at the top and bottom. Just measure the gap at the top and bottom, mark those widths on a picket, draw a line between them with a straightedge, and rip along the line with a circular saw. You may want to actually measure out and mark the location of each picket on the back of the rail, to make sure you don't wind up with some odd gap when you get to the end. A 3/4" wide picket is going to look mighty odd...

Only use

one screw at each position per picket, and don't space the pickets too close. The pickets will change width quite a bit over the seasons. Wet pickets installed with a 1/8" gap might have a 1/2" gap in the middle of a dry summer. Two points of attachment means the pickets will tear themselves apart, and tight gaps won't allow for expansion, again resulting in self-destruction. If you really want a tight privacy fence, you could use a router or dado blade to shiplap rabbet all the pickets, giving them a way to overlap without colliding. I did that for a gate, but it would be a lot of work for a long fence.

6. Install the other three rails. Cut them to length, and get a helper to stand on the other side of the fence to hold them in place while you drive the screws the remaining way home. You can use a clamp on the top rail, and maybe on the bottom rail, but it's best to just have someone push against you while you drive the screws in the middle rail. Be sure that the forces balance, and don't tighten the screws with the fence bowed because it will want to stay that way. It's best if the lumber is a little wet, because unless you want to remove, drill, and reinstall all those screws, At this point, remove the little 1/2" screws holding the rails on, and drill and install #8 x 2" stainless pan-head screws through the entire assembly.

7. Finishing touches. I put a 1x4 cap across the top, fastening it with four screws. This keeps rain from soaking into the ends of the pickets, and lends lateral strength to the fence. Trim the tops of the posts all at the same height from the top rail. I draw a line all the way around the post with a carpenter's square, and follow it with a handsaw. A post cap finishes off the job. I usually attach it with a couple of screws right through the top, because it's easy to remove if damaged, and the screws won't fail like some of the adhesives I've tried.

|

| A similar fence I built on a slope |